The Legacy of Landmines: Stories from EMERGENCY’s Patients

In conflict and post-conflict zones, landmines and other unexploded ordnance remain a threat to lives and livelihoods long after fighting has ceased.

In Afghanistan, we continue to treat victims of landmines in our surgical hospitals, providing high-quality medical and surgical care. In Iraq, our services include prosthetics and physiotherapy sessions that help people regain their independence.

All too often, the victims are children, who mistake the devices for toys or valuables.

Here, we share the some of our patients’ stories: the reality of what happens when a war “ends”.

APRIL 2025 | AFGHANISTAN

Many mine victims are children

“I was playing with some kids. I picked up a mine with my hands. The bomb exploded.” Nasratullah, 10 years old, lost two fingers to a landmine.

More than a quarter of Afghanistan remains contaminated by landmines, IEDs, cluster munitions—the explosive remnants left behind by decades of war. At EMERGENCY’s hospitals across the country, we continue to treat hundreds of patients with mine injuries every year.

Many of the victims are children.

“I wanted to bring apricots from the garden. Then, the mine exploded on me.” Abdullah, 13, was seriously injured in the blast. Both his grandfather and brother were killed.

In recent months, at least five European states – Poland, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and Finland – have announced their intention to withdraw from the Ottawa Convention, a treaty that bans both the production and use of anti-personnel landmines. Once a milestone in international law, the weakening of the Ottawa Convention threatens the long-term protection of civilians and health.

“When the explosion happened, I thought I was done for,” says 25-year-old Bashir, injured by a stray landmine while building a home for his family. “The country is full of mines. With the help of the doctors, some of us are healed.”

We are sharing stories from our patients from award-winning journalist Lynzy Billing, highlighting the long, violent legacy of war in Afghanistan.

APRIL 2024 | IRAQ

Aso Muhamad

“All it took was mistaking a mine for an ordinary object. I played with it for a few moments and touched the black plastic top when it exploded, throwing me metres away. Then screams, smoke, crying…”

At only 16 years old, Aso Muhamad lost both of his hands to a landmine. He lives with his family in Iraqi Kurdistan.

“When I was 12, I started working as a shepherd. My family could not afford to send me to school,” he says.

One winter morning, on his way home with his brother after taking their animals to pasture, his life changed completely.

“Seeing the stumps, all I did at first was cry. I was shocked to see myself like that.”

At our Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration Centre in Sulaymaniyah, Aso Muhamad has received two prostheses and regularly attends physiotherapy sessions.

Iraq continues to be among the most mine-contaminated countries in the world: 2,800 square kilometres of unexploded ordnance, a third in rural areas, put the lives of the population at risk every day.

AUGUST 2023 | AFGHANISTAN

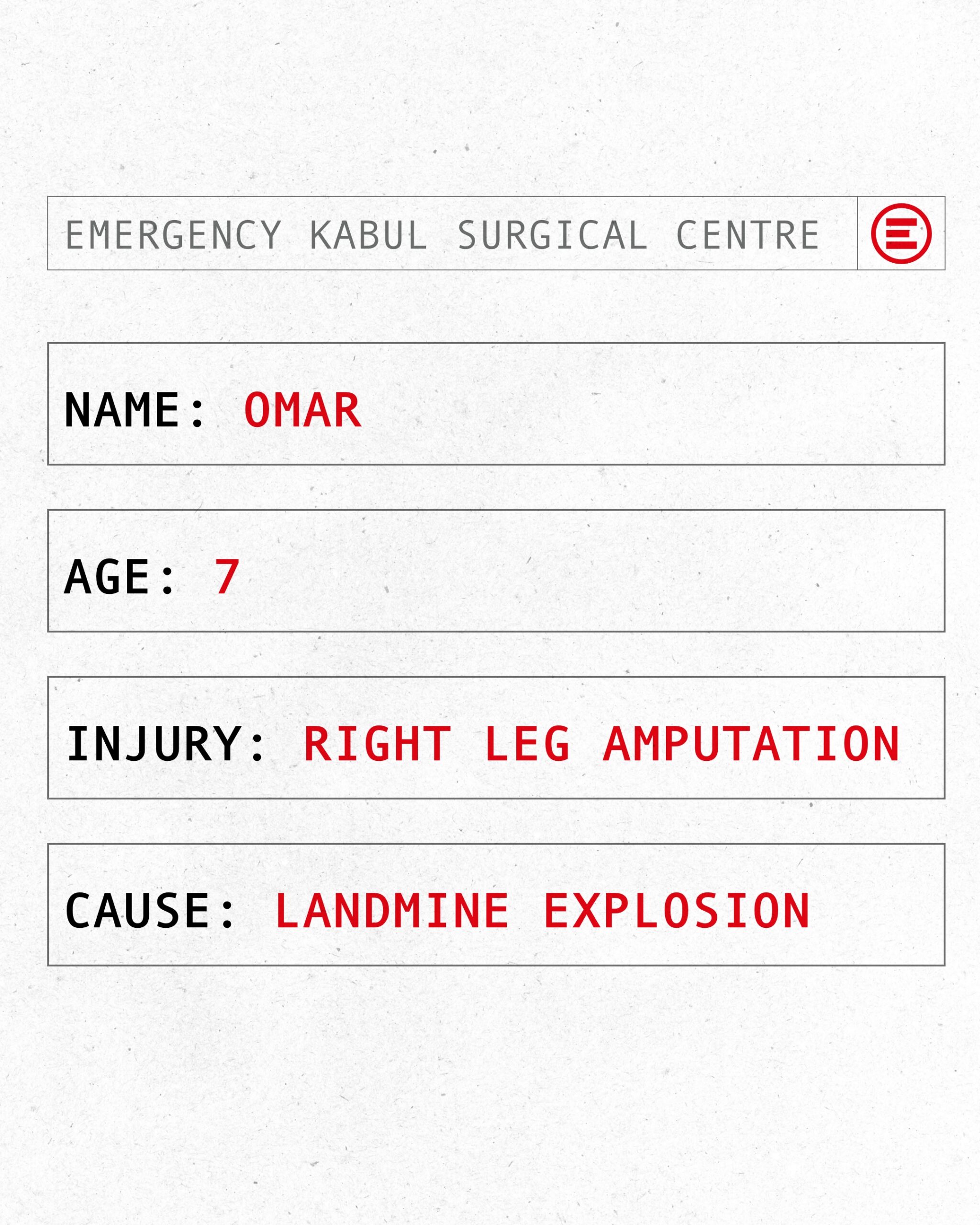

OMAR

The operation saved his life.

Seven-year-old Omar lives in Afghanistan, a country still recovering from more than four decades of war.

Omar and two of his family members were rushed to the Kabul Surgical Centre after a landmine exploded, just one of tens of thousands of unexploded ordnance littering the country. One of Omar’s brothers was killed by the explosion.

Omar arrived to the hospital with blast injuries all over his body. He was rushed into the operating theatre, where the surgeons had to amputate his right leg above the knee but saved his life.

His other family members were discharged a few weeks ago, but Omar has needed multiple operations and is continuing to recover.

His parents visit often. Unable to pay for treatment in other hospitals, EMERGENCY’s commitment to always providing free, high-quality care has been a lifeline for their family and so many others across Afghanistan.

APRIL 2023 | AFGHANISTAN

MOHAMMAD AND SHAMSIA

The children were playing in the garden when the IED exploded.

They had found an old metal device that they said looked like a big bullet, and threw it away. 13-year-old Mohammad and his sister, 4-year-old Shamsia, were the closest.

They come from a poor family in a remote village in Sangin district, Afghanistan. They had no way to bring the children to our clinic, so their uncle left to rent a car. Hours after they first sustained their injuries, Mohammad and Shamsia arrived at our First Aid Post, where our 24-hour ambulance then transported them to our Surgical Centre in Lashkar-Gah.

Both will need a long time to heal.

Shamsia has had surgery to repair vascular damage from severe fractures in both legs.

Mohammad’s right arm has been amputated below the elbow, and so have the fingers on his left hand. He has further injuries to his face, eyes and legs. But, our colleagues tell us, “The very next day, Mohammad was smiling with the nurses in the ICU.”

The siblings will spend the next few months using wheelchairs, waiting for their most serious wounds to heal so that they can start to walk again.

Long after the end of conflict, the explosive legacy of war continues to threaten innocent lives.

FEBRUARY 2023 | AFGHANISTAN

NABIULLAH

When a group of eight children between 2 and 10 years old arrived at our Kabul Surgical Centre, 7-year-old Nabiullah was among them. He was suffering from multiple shell injuries to his legs, abdomen and left hand.

Nabiullah’s family is from Sorabi, near Kabul. He stays home from school, helping earn money for his family and take care of his younger brothers.

Nabiullah was in a group of children collecting metal to sell. When they found a device, Nabiullah tried to open it with a rock and it exploded, injuring everyone standing close by.

After several surgeries, Nabiullah is now stable and recovering. When he spoke to his mother on the phone, he reassured her: “Don’t worry, I’m ok. I have both my legs, just my fingers are gone.”

Our staff describe him as brave, and full of smiles and laughter.